A Defence Policy for Uncertain Times

From Our North, Strong and Free/DND

From Our North, Strong and Free/DND

By Colin Robertson

POLICY MAGAZINE April 11, 2024

https://www.policymagazine.ca/

An ambassador from a NATO nation, having served in Canada for several years, recently made the following observation to me: That for a country with immense landmass – second only to Russia – the longest coastline fronting three oceans, and the tenth-biggest global economy, Canada carries a remarkably small stick when it comes to defence. “Are you that certain of the American security umbrella?” asked the ambassador.

It’s a good question but not one our new defence policy wants to address, at least not head-on.

So instead, after the ritual identification of the threats posed by Russia, China and climate change, the new policy says that “The most urgent and important task we face is in asserting Canada’s sovereignty in the Arctic.”

Promising more attention to our Arctic and High North is something successive American administrations have encouraged Ottawa to do. Indeed, US Ambassador David Cohen quickly and formally endorsed the new policy. Perhaps this is sufficient affirmation of continued American protection. But what if, come January 20, Donald Trump once again takes the oath of office?

While the instinctive reflex to this scenario is to fixate on our southern neighbour, it is easier and probably more politically astute to focus for now on our North, especially given our romantic attachment to it.

The Trudeau government has already made a down payment in renewed northern security with its 2022 promise of a $38.6 billion plan to modernize North American Aerospace Defense Command (NORAD), including Arctic and Polar Over-the-Horizon Radar systems over the next two decades.

In that sense Our North, Strong and Free is much more than an update to the 2017 Strong, Secure, Engaged defence policy. ‘Our North’ commits $8.1 billion over five years and promises another $73 billion over 20 years. If implemented, it will increase defence spending from 1.33 percent to 1.76 percent of GDP by 2029-30.

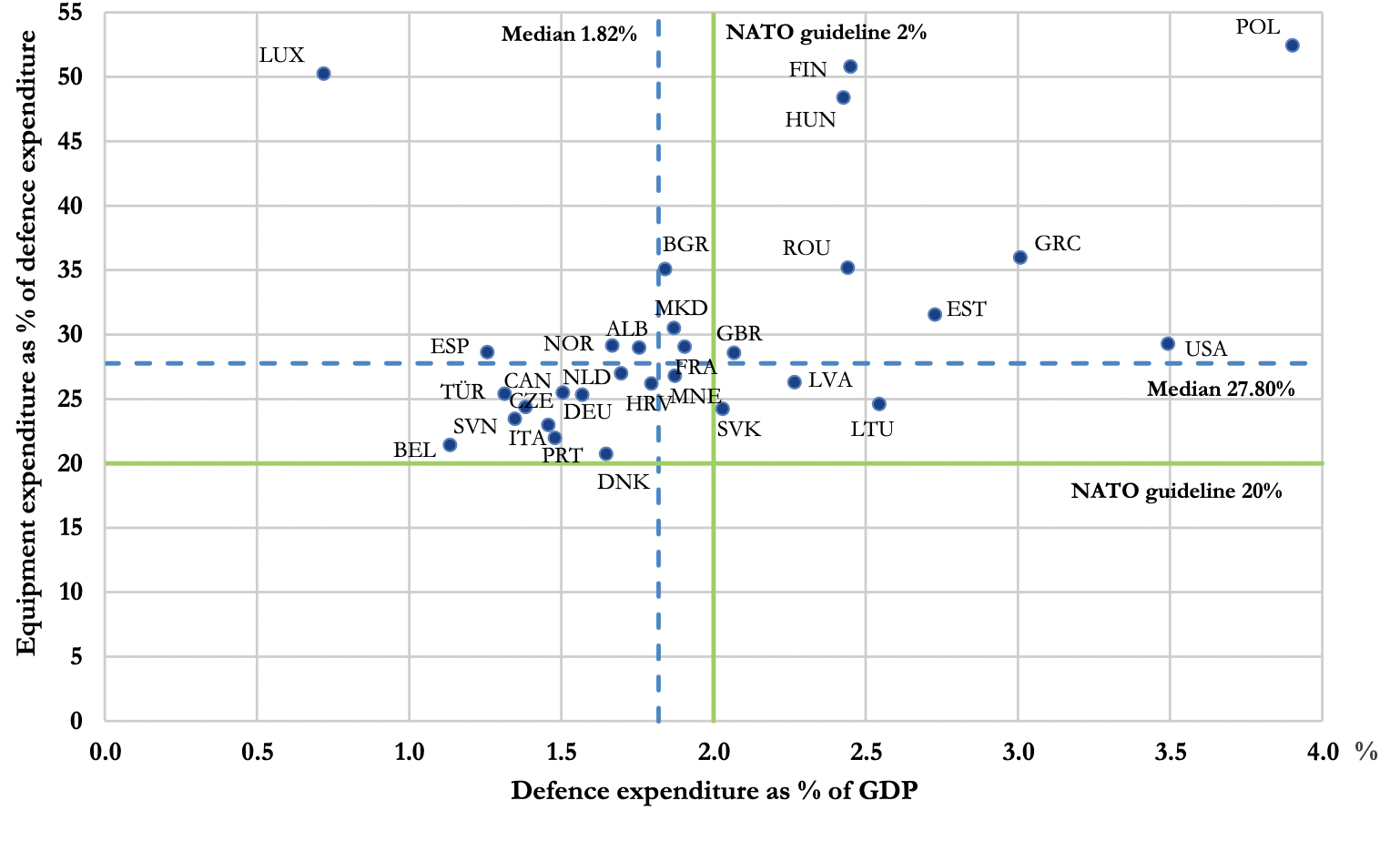

It’s not the 2 percent we agreed to at NATO’s Wales summit in 2014 and which has become such a point of contention in defence-spending debates but, as Prime Minister Stephen Harper said at the time, that 2 percent was ‘aspirational’. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau recommitted to the 2 percent again at last year’s Vilnius summit and we remain committed to get there. Eventually.

To put it in perspective: NATO figures show defence spending as a percentage of GDP for NATO Arctic Council nations as: US 3.24; Finland 2.46; Finland 2.3; Denmark 2.0; Norway 1.8; and Canada 1.33. By contrast, Russia spends 6 percent of GDP on its military. China, an observer to the Council, spends 1.7 percent.

As its subtitle proclaims, ‘Our North’ is ‘a renewed vision for Canadian defence’. However, as with the 2022 announcement, the real or ‘cash’ money is much less than the promised funding. The future funding is a promissory note for future governments to honour (or not).

Past investments by the Harper and Trudeau governments mean we now have some of our new offshore patrol ships at sea, our new maritime patrol aircraft are in production, our new surface combatants are approaching production and components for our new fighter jets are being manufactured. And there is money to ensure, in the meantime, that our aging frigates and submarines remain seaworthy. Our run-down bases will receive $10.2 billion over the next 20 years for repair and refurbishment.

We are also to get maritime sensors for ocean surveillance, tactical helicopter capability, northern operational support hubs, and airborne early warning aircraft. This is all necessary kit.

It also underlines the commitment to invest in our defence production industries, with $9.5 billion allotted to ‘made-in-Canada’ artillery ammunition and $9 billion to sustain military equipment.

Procurement is to get another review and money for more staff to speed up the process, something long advocated by the Canadian Association of Defence and Security Industries.

There is money to support the doubling of our NATO troop commitment in Latvia and for our participation in annual NATO exercises. The previously announced Halifax-based NATO Defence Innovation Accelerator for the North Atlantic is also to be funded.

While our NATO allies and partner nations in the Indo-Pacific who are leery of China will privately grumble about the Canadian inability to get to 2 percent, they understand that politics is the art of the possible.

We will also acquire a comprehensive worldwide satellite communication capability and establish a Forces and Communications Security Establishment joint cyberoperations capability. Cybersecurity is generally a no-brainer, especially given the disturbing revelations coming out of the inquiry into foreign interference.

Investment in the people of our Forces has been long overdue. Our recruitment and retention crisis means there is shortage of over 15,780 in a Force of 71,500 – more than 20%. There is money for housing and child care and a promise to look at the terms and conditions of service. ‘Culture change’, once set as the top priority, is now secondary to Forces readiness and operational capacity.

There is a promise (but no banked money) to explore options for a new fleet of submarines. Mr. Trudeau seems to suggest nuclear-powered submarines may be an option but, at an estimated $8 billion apiece, any future government will likely reach the same decision as the Mulroney government did in 1988-89 when we last explored this option with the Americans. While we may have AUKUS envy, technological collaboration on AI and other areas is probably the easier way into that tent.

While our NATO allies and partner nations in the Indo-Pacific who are leery about China will privately grumble about the Canadian inability to get to 2 percent, they understand that politics is the art of the possible. For the Trudeau government, its priority from the get-go has been social justice – $10 a day child care, doubling of money for Indigenous reconciliation, dental care, school food programs, and money for a range of housing-crisis fixes.

Defence spending has never been a Trudeau government priority. So, getting what we got is a testament to that minority of ministers – Anand, Blair, Champagne, Freeland, and Joly – who recognize the requirement for hard power, and a Chief of Defence Staff and service chiefs who speak truth to power. They are aided by dedicated civil servants as well as editorials and a series of recent public opinion polls that demonstrate ordinary Canadians also recognize the changing threat environment. All of this combined with increasingly less subtle pressure from the US and other allies helped to get the new policy and funding over the line.

Given the effort that went into defending our north, it is surprising, especially given this government’s commitment to a ‘whole of government’ approach, that we did not also see a more comprehensive strategy for the North. While our Arctic Council NATO partners have comprehensive strategies for their north, we are still waiting for the Arctic and Northern Policy Framework, announced just prior to the 2019 election, to be fleshed out.

Going forward, the government pledges to update the defence policy every four years (the normal life of a government) in “a more regular cycle of review and investment” and to bring forth a national security strategy with threat assessments. It would be the first since 2004 and it would bring us into alignment with our allies.

Notably missing from the 2017 defence policy was anything on ballistic missile defence. Now, we face the threat of hypersonic missiles. ‘Our North’ simply says “more work is needed to defend Canada and Canadians against growing air and missile threats.”

Peacekeeping, that many thought would be the hallmark of ‘Canada is back’ after the 2015 election, gets a totemic mention in reference to the 2017 Vancouver Principles on Peacekeeping.

This is unfortunate, as we could have opened the door to a re-endorsement of the 2005 adoption at the UN World Summit of ‘Responsibility to Protect’, or “R2P”, a very Canadian creation that complemented the Chrétien government’s magnificent Human Security Agenda (Land Mines Treaty, Child Soldiers Convention, and International Criminal Court).

But that was a time of muscular, Pearsonian initiative, led by a committed prime minister and skilled ministers, prepared to invest time and capital in initiatives aimed at prevention and mitigation of conflict. They also invested in relationships built through a robust development assistance program and a motivated, activist diplomatic service. A future government should once again champion human security and responsibility to protect, now more necessary than ever. That would signal ‘Canada is back’.

‘Our North’ is a transactional start in rearmament. While timid in ambition, lacking in urgency and quick to put off until tomorrow what should be done today, there is at least greater realism in its appreciation of our defence and security situation.

Geopolitics and climate could change for the better. The world could become kinder and gentler. And pigs may take flight. But in the meantime, more investment in defence bolsters deterrence and is our insurance against calamity.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.

The 2023 NATO Vilnius Summit/NATO

The 2023 NATO Vilnius Summit/NATO

Nick Etheridge by the unusable Hanoi Villa bomb shelter, December 1972

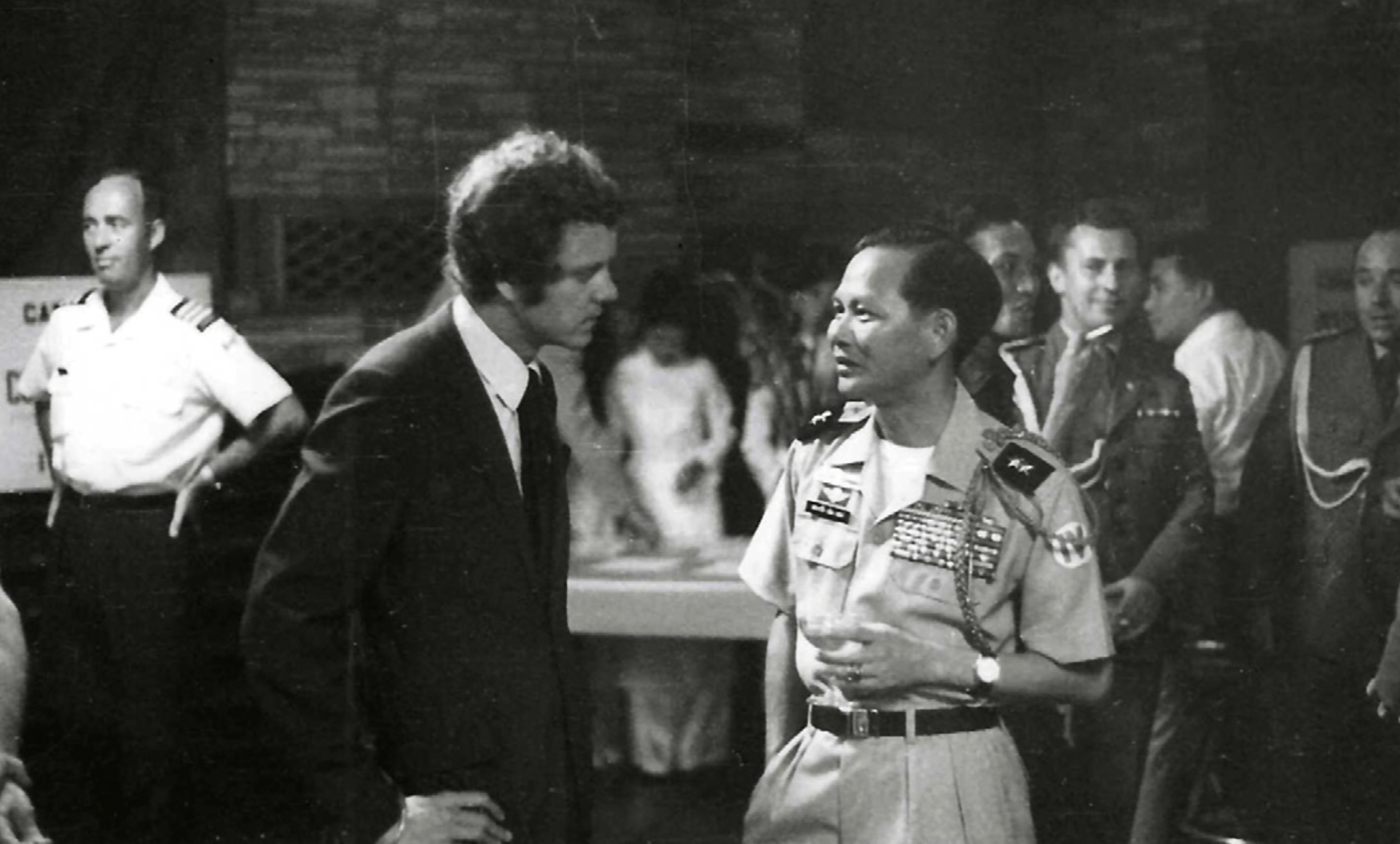

Nick Etheridge by the unusable Hanoi Villa bomb shelter, December 1972 Manfred von Nostitz talking to South Vietnamese General Nguyen Van Nghi in Can Tho, 1973

Manfred von Nostitz talking to South Vietnamese General Nguyen Van Nghi in Can Tho, 1973