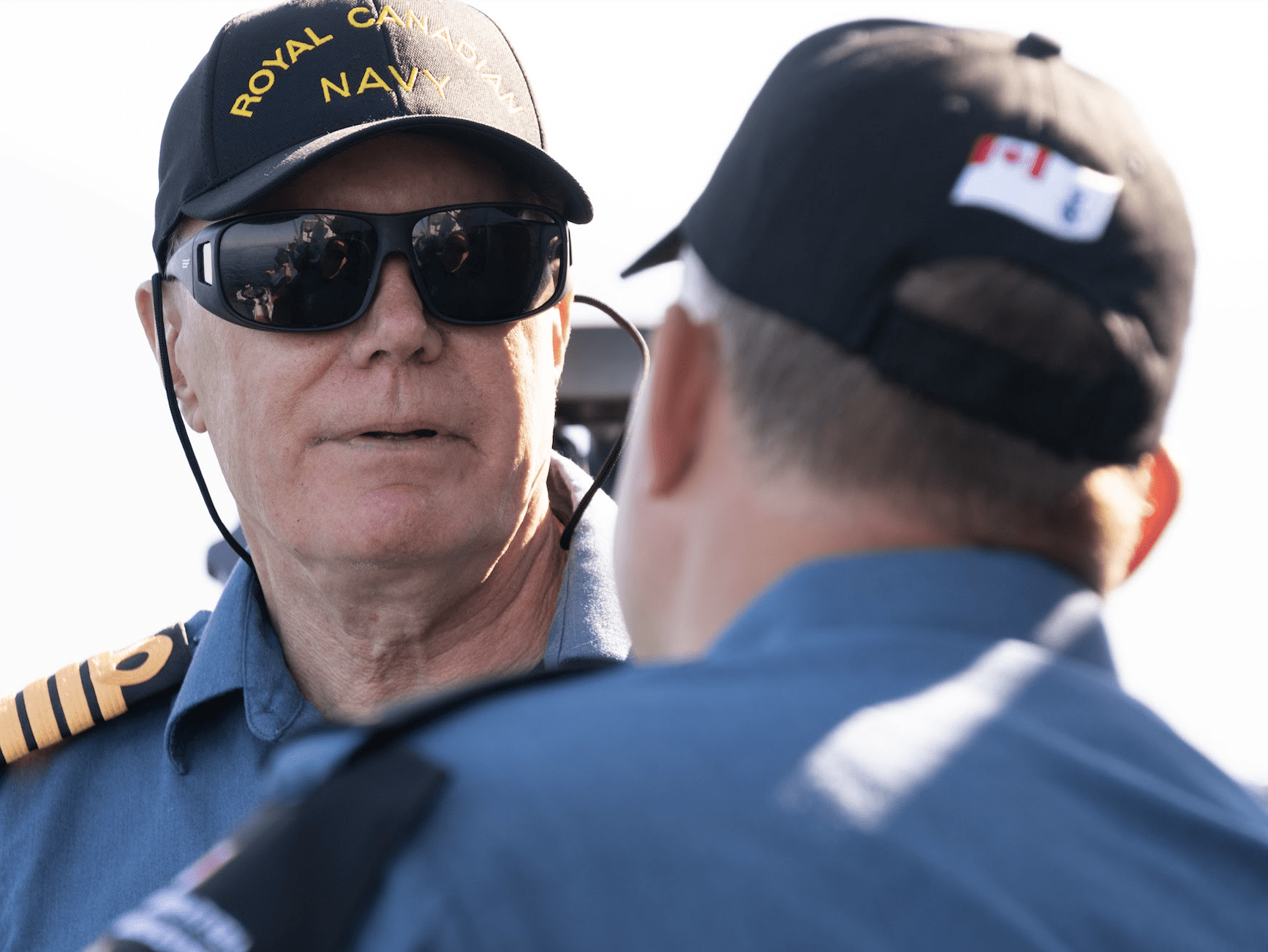

The author aboard the HMCS Winnipeg (Royal Canadian Navy)

The author aboard the HMCS Winnipeg (Royal Canadian Navy)

By Colin Robertson

POLICY MAGAZINE August 4, 2023

Spend time on one of Canada’s warships or submarines and you are struck by two things. First, despite heroic efforts at refurbishment, our marine hardware is past its best-before date. Second, the ingenuity, competence and teamwork of the men and women who adapt and improvise around that fact, and whose efforts ensure that Canada’s aging fleet can still ‘float, move and fight’, are awe-inspiring.

In July, I went to sea aboard HMCS Winnipeg — a 440-ft, Halifax-class frigate that has served the Royal Canadian Navy since 1996 — as a participant in the RCN’s Leaders at Sea program. We were seven men and seven women, mostly educators from schools, colleges and universities along with those active in community affairs and civic government.

We started with an early-morning tour of Esquimalt naval base. Located at the southern tip of Vancouver Island, overlooking the Strait of Juan de Fuca, Esquimalt has been the West Coast home of the Royal Canadian Navy since the Crimean War, first to the Royal Navy, and since 1909, to the Royal Canadian Navy. The next year, Canada acquired its first warships, HMCS Rainbow, which arrived in Esquimalt in November 1910, and HMCS Niobe stationed in Halifax. They were second-hand Royal Navy cruisers, a practice we would continue later in the purchase of our four Victoria-class submarines, two of which are now undergoing repair in the Esquimalt dry docks.

The next stop on base was to get outfitted with the naval combat uniform and seaboots that we wore for our three days at sea. Our spare kit, bulked by yellow life jackets, was stuffed in the green sea bags that we slung over our shoulders as we boarded HMCS Winnipeg.

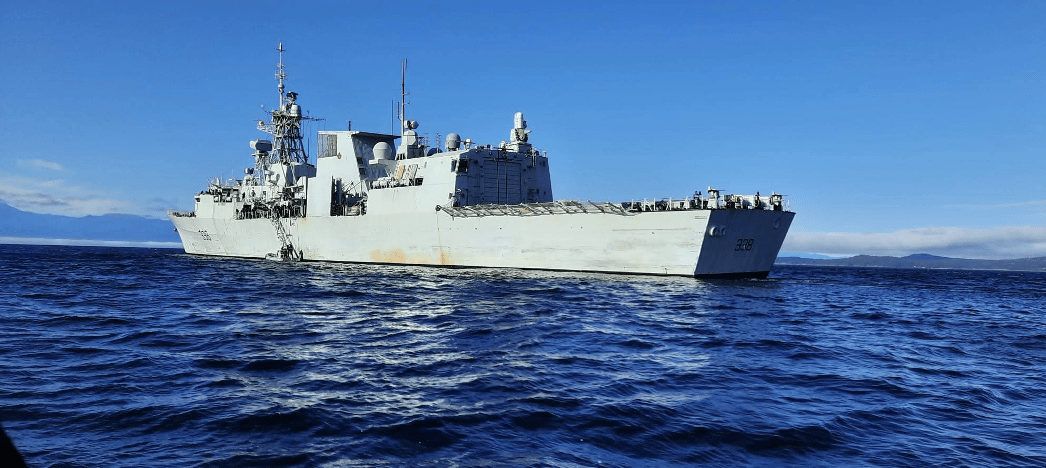

HMCS Winnipeg, a 440-ft Halifax-class frigate (Phil Bates)

HMCS Winnipeg, a 440-ft Halifax-class frigate (Phil Bates)

From a privileged spot on the bridge, we watched our departure from the harbour. We were impressed by the crew’s practised navigational skill and quiet calm as we threaded through the pleasure craft, cruise ships and container vessels, more of the latter than usual because of the port strike in Vancouver.

Rear Admiral Chris Robinson, who commands our Pacific fleet, and Commander Vince Pellerin, captain of HMCS Winnipeg, briefed us about our navy and the training role of HMCS Winnipeg before we explored the ship from stem to stern. The engine room had particular appeal to the engineers in our group. The bridge gave us a panoramic view and we got a chance to pilot the ship.

We met the ship’s physician’s assistant, who said the most common complaint she dealt with was seasickness. Fortunately, we enjoyed fair winds and following seas, as our route took us around Vancouver Island, spotting whales and revelling in the iconic coastline that inspired Emily Carr.

Time flew, with a full program that included watching a team from Naval Tactical Operations Group scale and board the ship on foot-wide ladders. We fired 16 rounds in target practice and participated in a firefighting drill. Firefighting is an essential, vital skill maintained with regular exercises for everyone aboard.

We ate heartily: breakfast of eggs, bacon, beans and French toast at 0700, ‘soup’ at 1000, a hot meal or salad bar at noon and then a hot supper at 1800. The fare is the same whether you eat in the crew’s cafeteria, the chiefs’ and petty officers’ mess or the officers’ wardroom.

The sleeping quarters before we made our beds (author)

Our berths were spartan: six to a room with hallway lockers and the washrooms — the ‘heads’ — a couple of corridors away. Day began at 0630 or 0700 but if you wanted a shower – three minutes maximum — and breakfast, you needed to be up well before the ‘wakey-wakey’ announcement.

On our final night we enjoyed a ‘Banyan’ – a barbecue dinner on the flight deck with the ship’s crew to celebrate the end of a deployment that had begun in June on exercise with allied navies, then continued its focus on training.

We returned to shore in a Zodiac – the ride is like a roller coaster on water and you need to hang onto your cap. Mine sailed into the drink where, to my good fortune, a sailor retrieved it.

On shore, we visited the Damage Control station where they create fires to improve skills. We met with the diving team, who defuse mines under water and also on land. It’s dangerous work. Sadly it took the life of navy diver Craig Blake in 2010 while he was defusing an IED outside Kandahar during the Afghan campaign.

HMCS Winnipeg is one of twelve all-purpose frigates that bear the names of cities from Vancouver to St. John’s. Built starting in the late eighties by Irving shipyard in Halifax and Davie in Quebec City, they were commissioned between1992-96 as our primary warship.

A CH-148 Cyclone conducting a sea rescue exercise/Phil Bates

A CH-148 Cyclone conducting a sea rescue exercise/Phil Bates

With crews of between 180-240, their anti-submarine warfare capacity is complemented by helicopters, originally the venerable Sea King, and since 2018, the Cyclones. We watched a Cyclone perform a sea rescue exercise.

Designed for the Cold War, our frigates have served Canada well thanks to those who keep them afloat. They will be replaced by fifteen surface combatants to be built after the six new offshore patrol ships are completed in 2025. Our four submarines, bought from the British in the 1990s, also need to be replaced. The navy would like to buy a dozen ‘off-the-shelf’ from an ally who makes them. Potential suppliers include Japan, Korea, France, Germany, Spain, and Sweden. Nuclear submarines such as those the Australians are building with the US and UK would do the job, especially under ice. The price-tag – estimates for the Australian submarines approach a trillion dollars — is beyond what our governments would countenance, although it would surely raise our defence spending from its current 1.3 percent to that elusive 2 percent of GDP with (20 percent spent on equipment and research and development) that NATO leaders re-committed to at the July Vilnius summit.

Navies traditionally fulfill three roles. A constabulary function: working with our Coast Guard in preserving law and order and performing search and rescue in our territorial waters is well understood. So is its military role in securing freedom of navigation on the high seas, and providing deterrence against piracy and rogue actors, often as part of, or as the lead in a multinational naval task force.

The RCN’s diplomatic role is not always understood or appreciated even by those who go to sea. Diplomacy is about creating contacts and networks for information, for persuasion and for negotiations that achieve and advance Canadian interests. This is why our navy figures prominently in the government’s new Indo-Pacific strategy.

Throughout my diplomatic career, I saw time and again the value of port visits by our warships, and especially the onboard events as an opportunity to enlarge our networks, cultivate our contacts and advance our trade and political objectives. We launched our office in San Diego aboard HMCS Regina as she returned from piracy and terrorist interdiction in the Gulf. It drew the local congressman, who chaired the House Armed Services committee, the mayor, the commanding US admiral, and significantly amplified our outreach.

In his message to the Department of National Defence, Canada’s new defence minister, Bill Blair, identified his top priorities as the Russian invasion of Ukraine, Chinese sabre-rattling in the Indo-Pacific and our need to exercise sovereignty in our Arctic. That includes NORAD modernization, delivering new equipment and the need to “take new, innovative measures to recruit and retain even more talented Canadians” to our Forces, while at the same time transforming military culture “to ensure that all of our people in uniform feel protected, respected, and empowered to serve.”

The navy needs help with recruitment. Its new one-year Navy Experience program, which includes time at sea, is a good initiative and should be attractive to those contemplating a ‘gap’ year. But it needs marketing. Parliamentarians should publicize it in their constituency householders. And, as I learned from the educators on this trip, there are synergies to be developed with colleges and technical institutions both in recruitment and training for the trades that are essential to our navy.

For a country with three oceans, the longest coastline in the world and an economy that increasingly relies on salt water for its exports and imports, our navy is indispensable.

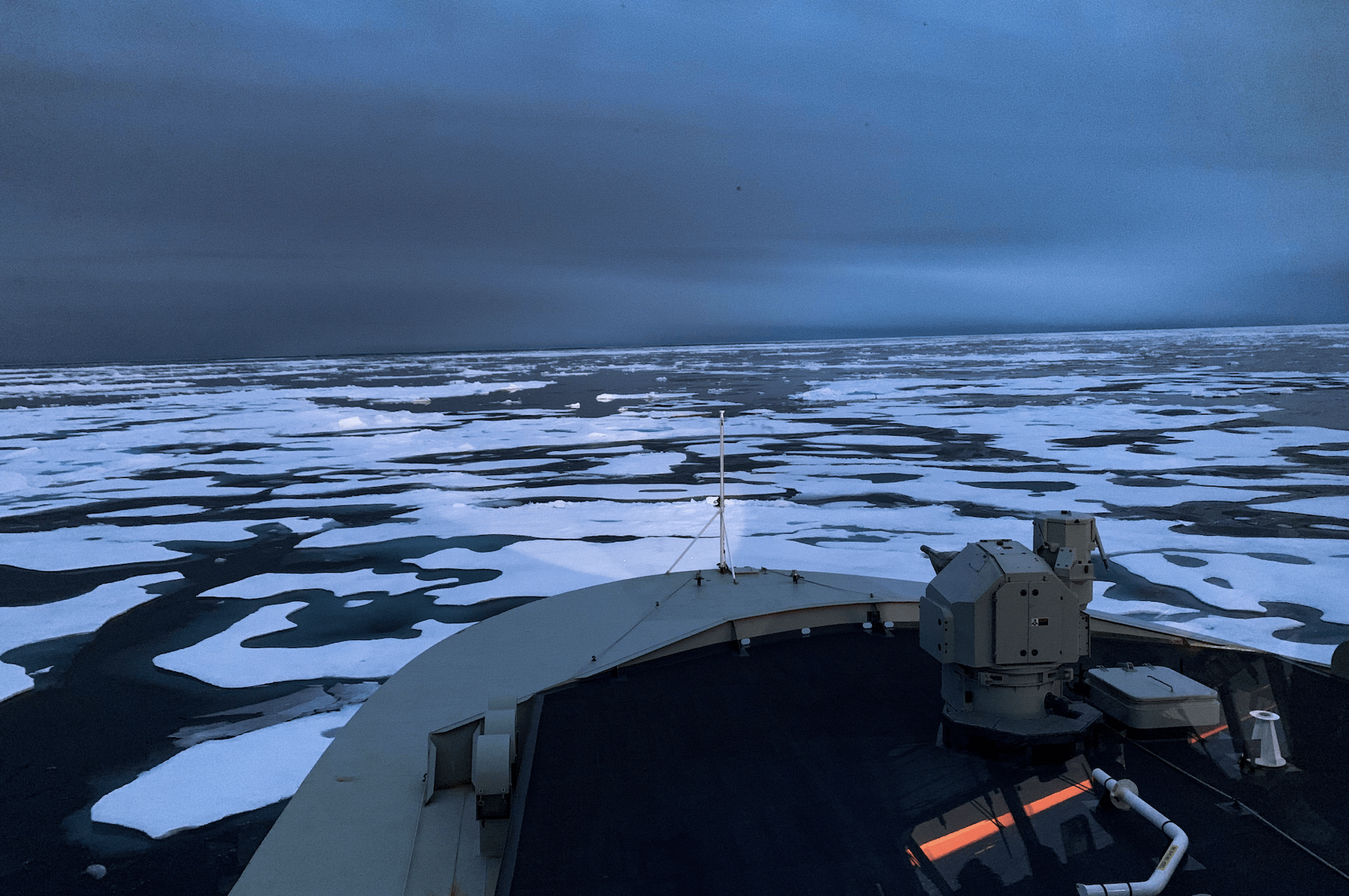

HMCS Harry DeWolf on ice-breaking duty in the Northwest passage/US Navy photo

HMCS Harry DeWolf on ice-breaking duty in the Northwest passage/US Navy photo

The sovereign territory it must defend is vast. Climate change is turning ice to water in our Arctic and there is now a pressing requirement to exercise the sovereignty we declare. Our new threat environment includes Russian submarines off the east coast and Chinese surveillance sonars in our Arctic.

The distance from Esquimalt to Nanisivik, the proposed new naval base in the Arctic, is about the same distance as from Esquimalt to Japan. To go from Halifax to Nanisivik is about the same distance as going from Halifax to London.

Our navy is also expected to sail the seven seas, with active operations as part of NATO in the Atlantic and Mediterranean, anti-piracy and terrorism in the Gulf, drug interdiction in the Caribbean and Pacific coast and now a greater presence in the Indo-Pacific. All in support of Canadian objectives. Yet with just 8400 personnel, the RCN is the smallest service in our Armed Forces.

Five years ago, appearing before the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence, the then Commander of the Royal Canadian Navy, Vice Admiral Ron Lloyd, posed to parliamentarians the following questions:

- Does Canada understand that its navy is one of its most flexible and persistent instruments of national power—in effect, our nation’s first responders?

- What kind of leadership role does Canada seek in contributing to global defence and security?

- Does Canada fully appreciate the range of threats that exists in the world today?

- Are the resources assigned to our armed forces well balanced to support Canada’s defence and foreign policy objectives?

- Finally, how much risk is Canada willing to accept when balancing resources and capabilities?

These questions have lost none of their relevance. They should be a starting point in the much-anticipated Defence Policy Update that Mr. Blair promises “in the coming months”.

Those who serve in our Navy are ‘ready, aye, ready’. But after decades of scrimping by successive governments, can we say the same of our political leadership?

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa. He is also an Honorary Captain in the Royal Canadian Navy.