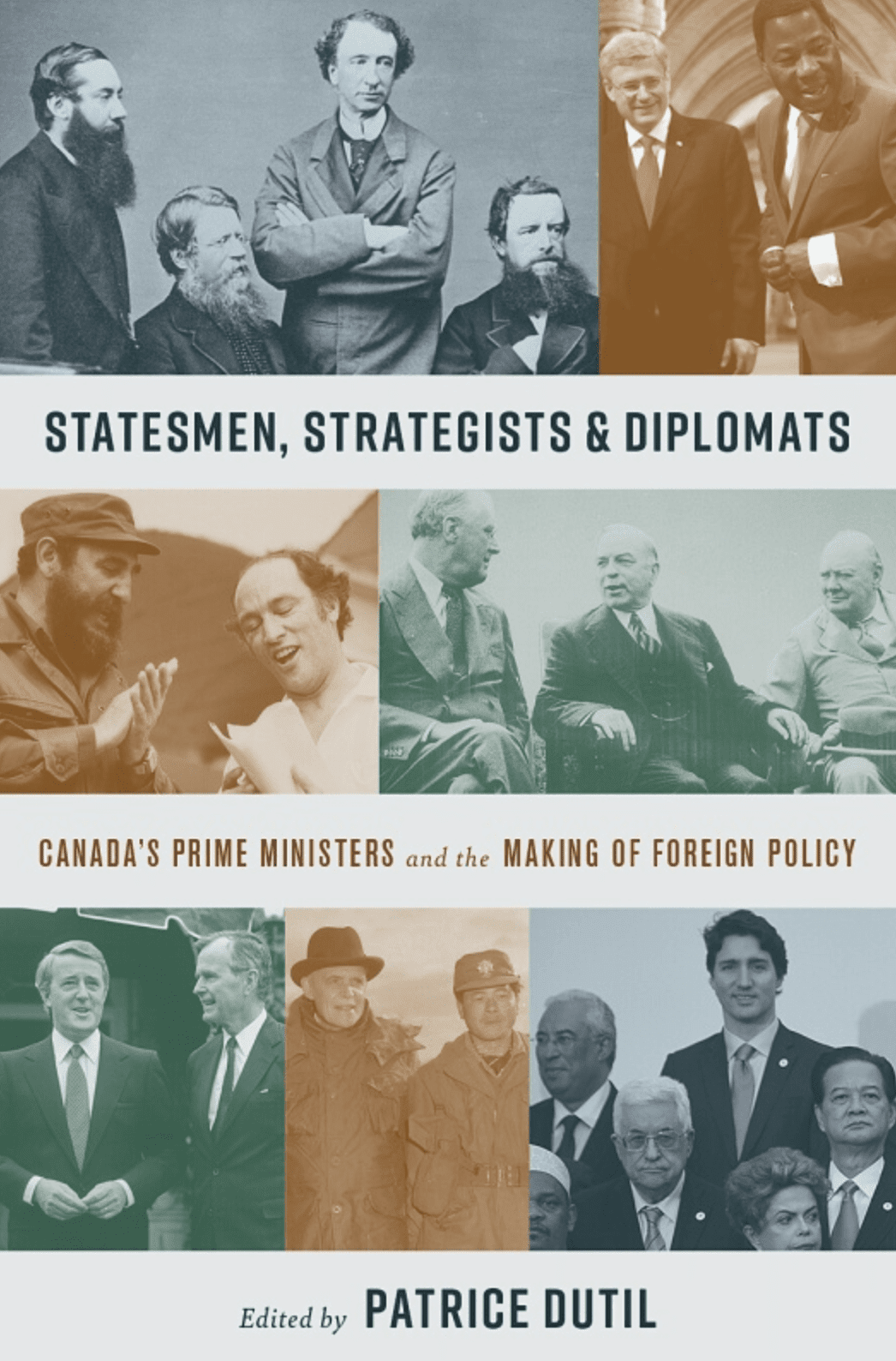

Statesmen, Strategists & Diplomats: Canada’s Prime Ministers and the Making of Foreign Policy

Edited by Patrice Dutil

UBC Press/June 2023

POLICY MAGAZINE Reviewed by Colin Robertson

September 3, 2023

A NATO-member ambassador asked me what book she should read to learn more about our prime ministers and their foreign policies. She was not the first ambassador to recognize that, in any Canadian government, prime ministers have the most profound effect on the direction of foreign policy. Certainly, more than the revolving door of foreign ministers.

I now have an answer for that ambassador and for anyone seeking insight into our prime ministers and their foreign policies: Statesmen, Strategists & Diplomats: Canada’s Prime Ministers and the Making of Foreign Policy (UBC, 2023), edited by Patrice Dutil, professor in the Department of Politics and Public Administration at Toronto Metropolitan University

Only those prime ministers who formed governments after winning an election are covered in the book. In a couple of cases – Sir John A. Macdonald with Alexander Mackenzie and Stephen Harper with Justin Trudeau – the approach is comparative. It probably would have been better to give each his own chapter. Each chapter begins with a summary chart of legacies in terms of structure, policy and style. The fifteen authors also collectively assess the prime ministers based on eleven questions.

Louis St-Laurent comes out as most ‘successful’, followed by Mackenzie King and Brian Mulroney. St-Laurent’s 1947 Gray Lecture was delivered while he was foreign minister. I tell new ambassadors to Canada to read it as it lays out the contours that still guide Canadian foreign policy: balancing the US relationship with a multilateralism that puts the accent on humanism, while always, always keeping an eye to national unity. It was St-Laurent’s speech, but it also reflected the view of his deputy minister, Lester Pearson, who would serve as St-Laurent’s sole foreign minister for nearly nine years.

I would have thought that Pearson, awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in resolving the Suez crisis, would rank higher but as the authors point out, the assessment is not on lifetime achievement but rather their time as prime minster. Pearson does get a mention, along with St-Laurent and Mulroney, as a ‘foreign policy superstar’.

I’d have given Jean Chrétien and Robert Borden higher grades. Borden got us a presence, if not a full place, at the Versailles Treaty table because of the blood and treasure we’d contributed during World War I. Borden’s personal efforts apparently included lifting up Lloyd George by his lapels to make a point. As historian Bob Plamondon has written, Chrétien kept us out of Iraq and gave his foreign ministers the backing needed for the Ottawa Treaty on land mines and then the Smart Border Declaration. Chrétien was underestimated during his career, to his adversaries’ regret.

In the bottom tranche are John Diefenbaker, R. B. Bennett, Stephen Harper and Justin Trudeau. Judgements on contemporary leaders are always tricky but, as veteran diplomat and Policy contributor Jeremy Kinsman recently observed in these pages, “while Trudeau is now the dean of G7 leaders, longevity in office hasn’t made him an international leader of consequence.”

That prime ministers play a central role in the direction of foreign policy is no surprise. Prime ministers in Westminster governments, whether with a majority or managing a minority, are recognized, writes Dutil, as ‘typically wielding enormous power’.

Foreign policy can be a point of difference, as with the division on the imperial ties in 1926, on acquiring nuclear warheads in 1962-63, and on free trade in 1911 and 1988. But, generally, there is more continuity than change in foreign policy, if not in style, as is illustrated in the comparative looks at Macdonald and Mackenzie, and Harper and Trudeau.

There are also factors particular to Canada: national unity and the preoccupation with Quebec; the imperatives of diaspora politics; and, always, the presence and preponderant place in all foreign-policy making of the United States. Confederation was, in large part, a strategic response to the threat of the Union Army. Fresh from Civil War, there was real concern that the US would complete the ‘manifest destiny’ that many Americans thought was both inevitable and their right.

What is a surprise to many prime ministers, and Dutil specifically cites Stephen Harper, is how much time they must devote to external affairs. It is, says Dutil, a recognition that that “‘external’ sits like a giant iceberg on the prime minister’s agenda”.

Part of this, of course, is that Canada’s foreign policy, like those of other nations, is also a reflection of domestic policy. For Mackenzie King foreign policy goals were “extensions of domestic policy”. Lester Pearson called foreign policy “domestic policy with its hat on”. Pierre Trudeau described it as “the extension abroad of national policies”. His son has certainly followed this approach. Justin Trudeau’s speeches to the UN with their focus on gender, the indigenous and climate reflect his domestic priorities.

The authors’ analysis is usually sound but I find awkward the statement that John Manley and Bill Graham — who served as Jean Chrétien’s foreign ministers after André Ouellet and Lloyd Axworthy — “were distinguished from the first in their relative lack of Parliamentary experience.” Manley had spent twelve years in parliament, four years in opposition, and was then industry minister. As foreign minister, he personally negotiated the Smart Border accord in a year. He left to become finance minister and deputy prime minister. Graham served over eight years in Parliament, shining as chair of the foreign affairs committee, before he succeeded Manley. Graham would become defence minister and manage the Afghanistan war before his eventual retirement as interim Liberal leader. Manley and Graham were able parliamentarians.

Dutil has done an excellent job both in selecting his fellow scholarly contributors and in producing a readable account. The book is meticulously footnoted for those wanting more with over 1200 references drawing on both original and secondary sources. There is also a moving tribute to the late Greg Donaghy, who passed away in 2020, and to whom the book is dedicated.

Dutil concludes that Canadian prime ministers who aspire to become statesmen must be strategists, meaning having vision and ideas. They also need to be diplomats “in the day-to-day testing of international relations” which means patience and perseverance — both hard for politicians. I’d add two more qualities: discipline and focus.

Time and chance also enter into the equation. But when it all comes together, as Dutil and his fellow contributors demonstrate in Statesmen, Strategists & Diplomats, then Canada has been able to punch above and beyond its weight.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.