POLICY MAGAZINE Colin Robertson October 12, 2023

“It is genocide – what Russian occupiers are doing to Ukraine.”

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky addressing the Canadian Parliament, September 22, 2023

To win the war against Russia and reclaim its territorial sovereignty, Ukraine needs a continuous flow of arms and money from the West. In the longer term, that support must transition to investment in reconstruction, preferably with Ukraine as a member of both the European Union and NATO.

The immediate challenge is arms. It is complicated by two things: Western arsenals are exhausted and armaments are not being produced or delivered quickly enough to support the Ukrainian counteroffensive. NATO leaders are committed to improving force capacity and capability but it requires action now with attention to improving production and supply chain efficiency.

As we have seen in other situations, it is the US, still the ‘arsenal of democracy’, that ends up carrying the burden of leadership, including supplying arms. According to the Kiel Institute’s Ukraine Support Tracker, the United States gives the bulk of military aid (over €42 billion). The EU is paying the bills (over €77 billion) to keep Ukraine operating, although the priority now needs to be on furnishing arms.

The flow of US arms is threatened by dysfunction in the US Congress. Funding for Ukraine is collateral damage in the internecine Republican party struggle that deposed Speaker Kevin McCarthy and could shut down the US government in mid-November if they can’t agree on financing its operations.

The Allies look at the US and echo the concern expressed by former Defense Secretary Robert Gates in Foreign Affairs that “dysfunction has made American power erratic and unreliable, practically inviting risk-prone autocrats to place dangerous bets —with potentially catastrophic effects.”

With US funding for Ukraine uncertain, the rest of NATO — Europe and Canada — need to immediately look to how they can boost their own production to meet the shortfall. The Europeans have long spoken about their desire for ‘strategic autonomy’. It starts with taking ‘strategic responsibility’ of meeting the shortfall arms if American supplies are interrupted.

‘Strategic responsibility’ also means the momentum for Ukrainian membership in the European Union and NATO cannot waver.

If wars teach us anything, it is that all plans tend to end after the first contact or, in the words of combat strategist Mike Tyson, “Everyone has a plan until they get punched in the mouth.”

For Europe, events on the periphery throughout history have always had an impact. If the war in Ukraine has given new meaning to NATO, bringing in Ukraine continues Europe’s move eastwards, even as it grapples with containing the flow of migrants on its southern frontiers as well as how to decouple from dependence on Russian energy, and how to de-risk from China.

Invoking the “call of history” in her annual address to Parliament in September, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said that Ukraine’s future is “in the Union”. The EU’s 27 foreign ministers met recently in Kyiv to demonstrate, as French Foreign Minister Catherine Colonna put it, “our resolute and lasting support for Ukraine, until it can win. It is also a message to Russia”, continued Colonna, “that it should not count on our weariness. We will be there for a long time to come.”

Accession talks could begin as soon as December. Ukraine is required to meet seven conditions laid out by the European Commission, including judicial reforms and anti-corruption measures. In 2022, Transparemcy International scored Ukraine near the bottom in its corruption index, only a couple of points ahead of Russia. Ukraine currently meets only two of the EU conditions. Both financial and technical support from Canada and the allies is essential, especially when it comes to transparency and good governance.

The war in Ukraine is challenging the EU and rekindling debate on core values such as an independent judiciary and a free press while underlining the importance of collective security. It is also pointing to the backsliders — Viktor Orban in Hungary and the Law and Justice government in Poland — that defy these values with little sanction.

I know from conversations with Biden when he was chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that he is an internationalist, committed to American leadership of the alliances. It is baked into his sense of where the US needs to be now and in the future.

Then, there is the cost. Ukraine would be the first new EU member since Croatia joined in 2013. Accession would entitle Ukraine to about €186 billion over seven years, according to internal estimates of the Union’s common budget.

There will be strong pressure from the other states awaiting membership: Turkey (since 1999), North Macedonia (2005), Montenegro (2010), Serbia (2012), Albania (2014), Moldova (2022), and Bosnia and Herzegovina (2022). Georgia also wants in.

Adding all nine would cost €256.8 billion. “All member states”, the EU studyconcluded, “will have to pay more to and receive less from the EU budget; many member states who are currently net receivers will become net contributors.” As Canadians know, redistribution — or what we call equalization — is controversial, both politically and economically.

Once derided by French president Emmanuel Macron as ‘brain-dead’, NATO is resurrected.

As the addition of Finland and Sweden demonstrates, the debate about how best to manage European defence and security is through NATO. At its Vilnius summit in July, the Alliance’s 31 members committed to investing at least 2% of their GDP annually on defence. More members are following Germany’s U-turn or “zeitenwende” on defence spending but they need to act now so that next year’s NATO summit in Washington is truly a celebration of 75 years of the world’s most enduring collective security pact.

Europeans and Canadians need to keep asking themselves not just how to keep the US fully engaged in NATO, but what they need to do to defend themselves as US strategic focus becomes increasingly Sino-centric.

For Europe, this means taking on far more strategic responsibility for the Middle East and North Africa and closer political-military ties with Asian democracies. For Canadians, this means real attention to meeting our NATO obligations and the resources necessary for NORAD modernization.

The war is also influencing developments in the Indo-Pacific with the US boosting its existing alliances with Japan and Korea, rejuvenating the QUAD, and creating AUKUS. Again, if Canada wants to participate in these forums it needs to increase capacity of our Forces, especially that of our navy.

After the debacle of the 2021 Afghanistan withdrawal that likely encouraged Putin’s adventurism, President Joe Biden is reasserting American leadership within the alliances.

But, as we witness in the congressional debates on funding the war, many in both parties want the priority to be fixing America’s domestic problems such as the cost of living, health care and migration. There is also a debate that the national security focus should be on the threat posed first by China, and then Russia, North Korea and Iran. A messy world – Russia vs. Ukraine and now Hamas vs. Israel — only encourages the insular, if not isolationist, instinct in America.

Biden’s 2024 election strategy is deeply entwined with his success in organizing the West’s response to Putin’s invasion. I know from conversations with Biden when he was chair of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee that he is an internationalist, committed to American leadership of the alliances. It is baked into his sense of where the US needs to be now and in the future. Biden’s vision of the global status quo is as a battle between democracy and autocracy. Ukraine is important but the challenge of China is the defining foreign policy issue of his presidency.

In Russia, a reckless Vladimir Putin is a dangerous Vladimir Putin. He has developed a messianic streak that is driving Russian expansionism. The abortive Prigozhin coup was the most significant challenge since he took power in 1999. The requirement to focus resources on the war has meant a loss of influence elsewhere. For Putin, a loss in Ukraine would be personally catastrophic. Calculating how he can tilt elections in the democracies to suit his interests and do what he can to ensure a Trump victory in 2024 will require constant vigilance and a united push-back on the part of the West.

For a China suffering from a post-COVID economic hangover, the war has brought cheap Russian energy and provided Chinese military planners with intelligence on tactics, sanctions and military capacity. Stoking nationalism at home, Xi continues to ramp up his military, aggressively pushing Beijing’s weight in its neighborhood especially against Taiwan. Ironically, the longer the war goes on, the weaker Russia becomes in Siberia and the Far East, allowing China to increase its influence there.

Canada has done right by Ukraine. Now, we need to think about what we can do to produce more armaments and then what we can bring to the massive reconstruction effort, including expertise in building resilient electrical grids, governance reform, combatting corruption and bolstering democratic institutions.

The goal of Canada and the allies must be to anchor a strong and prosperous Ukraine within a Europe that also provides a barrier against the expansionary impulses that drive Russian foreign policy. This task will take financial and military commitments requiring long-term sacrifice and perseverance. The ultimate goal is a return to a rules-based order not just in Europe but elsewhere. But that requires a Ukrainian victory and, for now, that means getting more arms to Ukraine.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a fellow and host of the Global Exchange podcast with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.

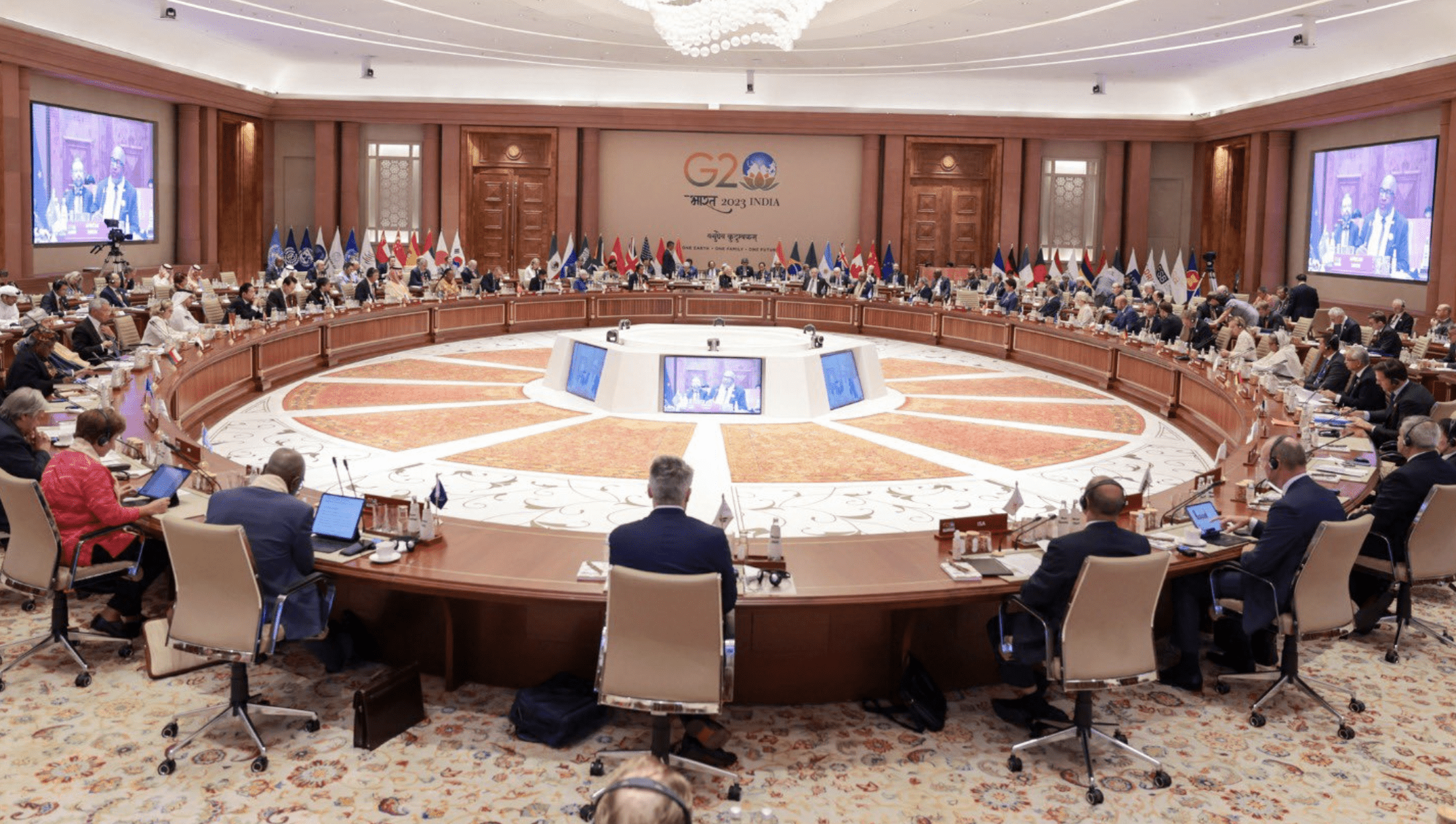

The G20 Leaders’ Summit in New Delhi/@G20org

The G20 Leaders’ Summit in New Delhi/@G20org

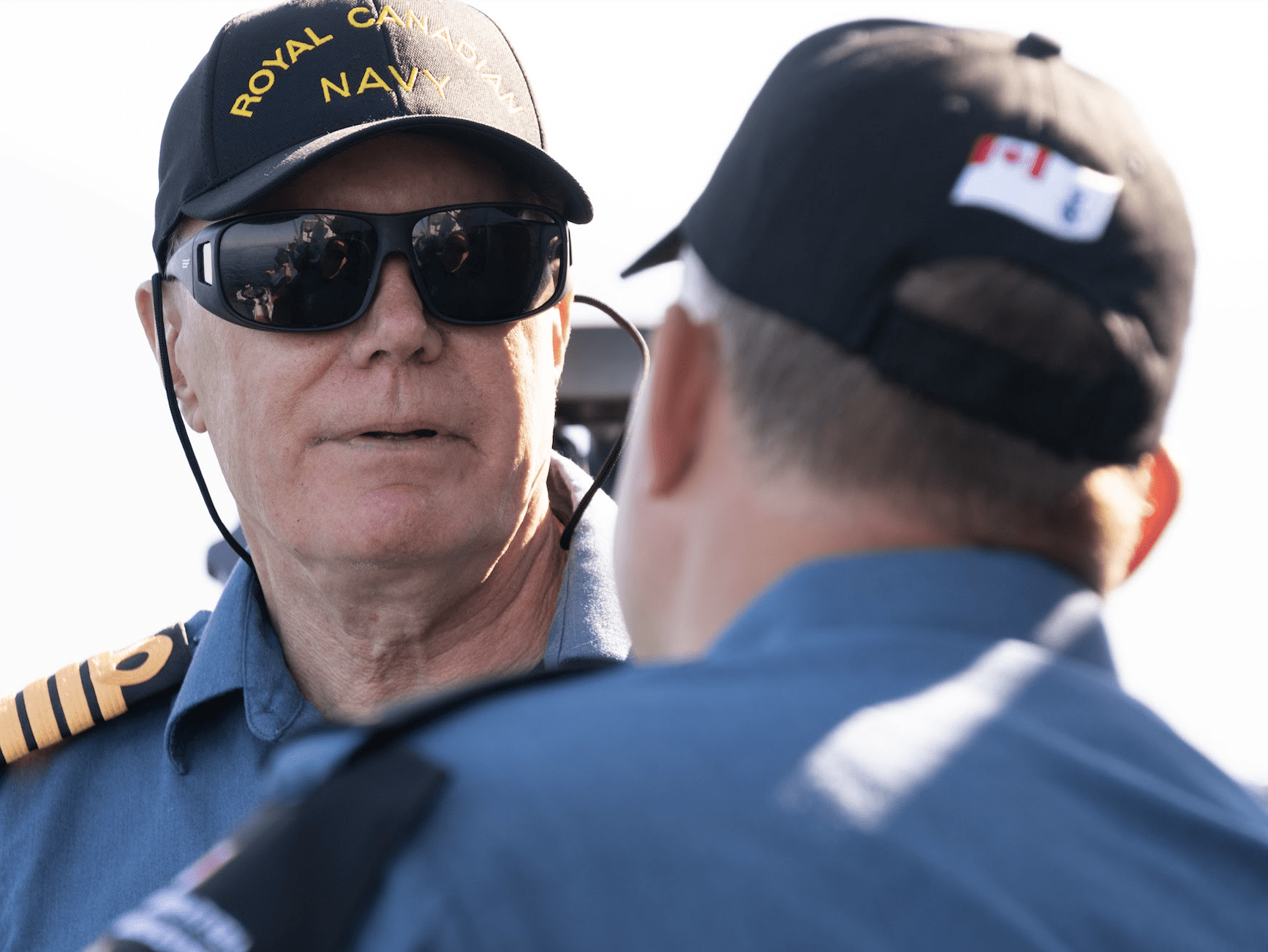

The author aboard the HMCS Winnipeg (Royal Canadian Navy)

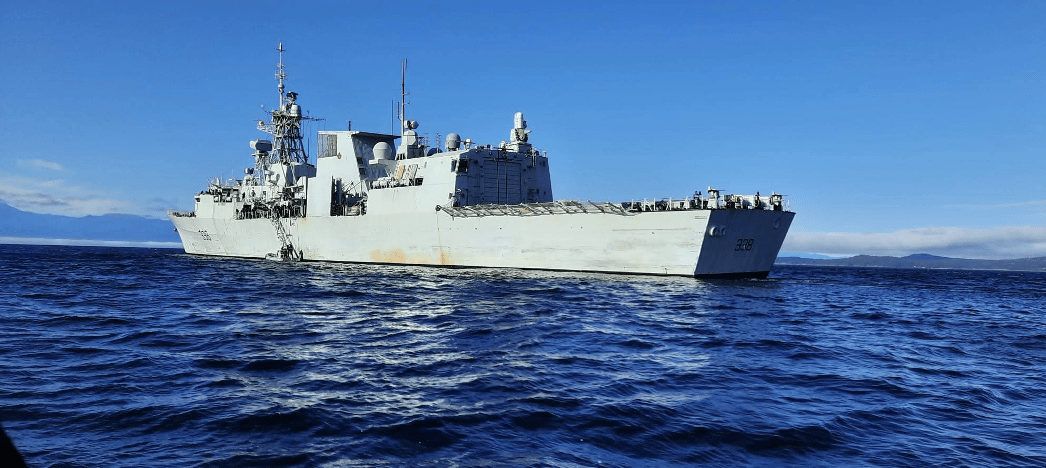

The author aboard the HMCS Winnipeg (Royal Canadian Navy) HMCS Winnipeg, a 440-ft Halifax-class frigate (Phil Bates)

HMCS Winnipeg, a 440-ft Halifax-class frigate (Phil Bates)

A CH-148 Cyclone conducting a sea rescue exercise/Phil Bates

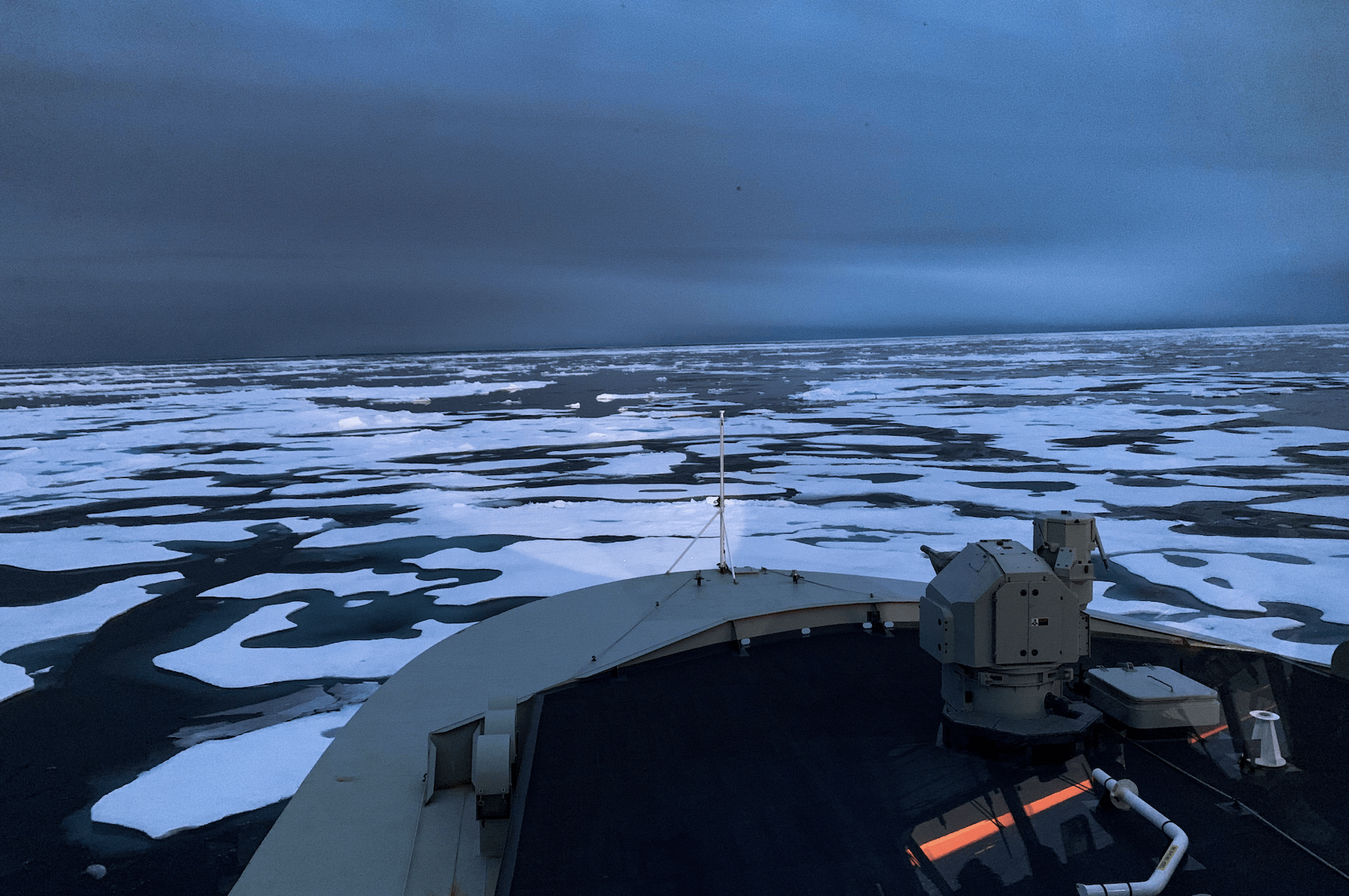

A CH-148 Cyclone conducting a sea rescue exercise/Phil Bates HMCS Harry DeWolf on ice-breaking duty in the Northwest passage/US Navy photo

HMCS Harry DeWolf on ice-breaking duty in the Northwest passage/US Navy photo