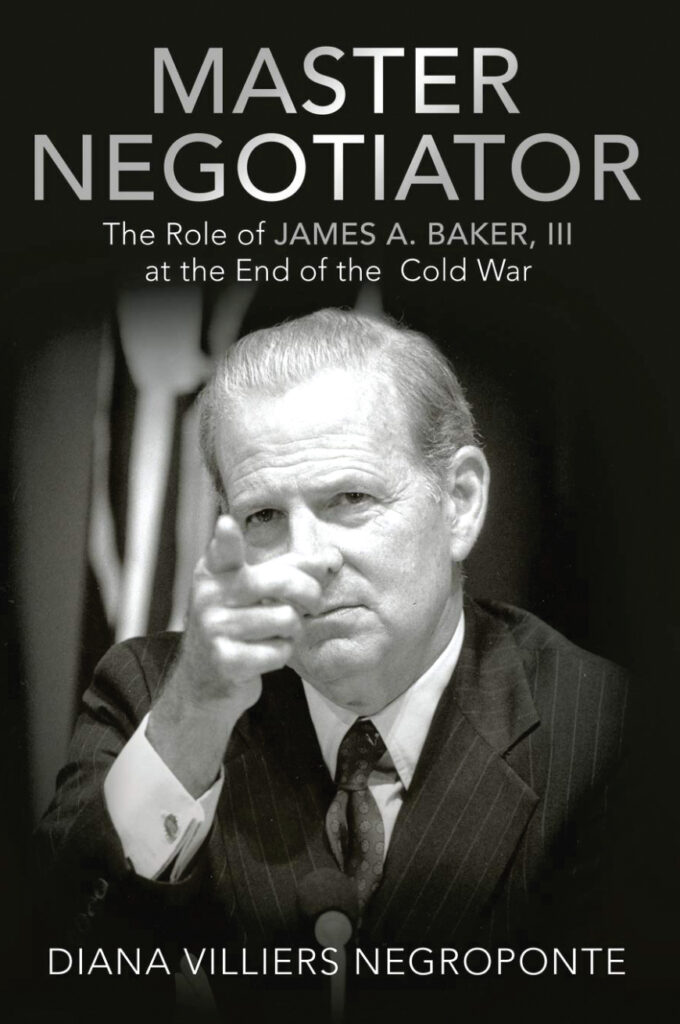

Master Negotiator: The Role of James A. Baker, III at the End of the Cold War

By Diana Villiers Negroponte

Archway/2020

Reviewed by Colin Robertson

Master Negotiator is a gem of a book by Diana Villiers Negroponte on the critical role of James A. Baker, III, in ending the Cold War during his almost four years as secretary of state in the administration of George H. W. Bush.

Unlike most western democracies, where foreign affairs are managed by professional diplomats, the American system relies to a much greater degree on its political class. They occupy most of the senior positions in the State Department as well as at their embassies. Negroponte’s book helps explain how this system works. Under the stewardship of Jim Baker, it had more successes than failures, especially in the critical area of arms control with the end of the Soviet Union.

Succinct but comprehensive, Master Negotiator is a meticulous, 360-page study. Based on interviews with most of the American principals of the period, with a deep dive into the archives, personal papers of the participants as well as French and German sources. It includes, for example the minutes of notes between senior American and Soviet leaders.

There are colourful vignettes, including the moment when Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev invites Baker and Ambassador Robert Strauss to drink, sweat, and soak bare naked in his personal sauna. As Nazarbayev whacks Baker on the back with bark twigs before plunging into the steam bath, Strauss, a fellow Texan, jokes to the security detail, “Get me the President on the phone! His Secretary of State is buck naked and he’s being beaten by the President of Kazakhstan.”

Diana Negroponte, a scholar on Latin America, is a Global Fellow at the Wilson Center in Washington and she dedicates the book to her husband, Ambassador John Negroponte. John Negroponte played an important supporting role during this period, having served President Reagan as Deputy National Security Advisor and then as US Ambassador to Mexico during the GHW Bush administration.

The 10 chapters in Master Negotiator address the key international issues: German reunification, China and Tiananmen Square, mobilizing international support during the Gulf War, the Arab-Israeli “distance”, arms control, and the breakup of Yugoslavia.

Surprisingly, the NAFTA negotiation in 1991-92 gets little attention, but as Negroponte concludes, Baker had more than enough on his plate and he was comfortable leaving the negotiations in the hands of the able US Trade Representative, Carla Hills.

The main focus of the book, appropriately, is on efforts to avoid disaster as the Soviet Union imploded. Negroponte points out that scholars still disagree on what caused its dissolution: Ronald Reagan’s SDI strategy; the stagnation of the Soviet economy and Mikhail Gorbachev’s radical domestic reforms; broad systemic changes including the diminishing conflict between capitalism and communism as nationalism, religions and the rights of people grew in importance. (Interestingly, the answer I heard most often during a recent trip to Eastern Europe as to what ended the Soviet Union was a variation of “Blue jeans, the mini skirt and rock ‘n roll.”)

This was the world that James Baker had to manage. Born in Houston, educated at Princeton and the University of Texas law school, he served in the Marines and rose to become a captain in the Reserve while practising law. His graduate thesis contrasted Ernest Bevin (union leader, British foreign secretary) and Aneurin Bevan (Welsh Labour Party leader, instrumental in founding of the National Health Service). Negroponte concludes that Baker preferred Bevin’s pragmatism but that the distinctions between the two men reflected the tension within Baker’s life and his preference for achieving his goals through purposeful and pragmatic steps.

A confidant and friend of George H. W. Bush, Baker served in the Nixon and Ford administrations, ran Bush’s unsuccessful bid for the presidency in 1980 and then served Ronald Reagan as both Treasury Secretary — playing the role of “closer” in the final days of the Canada-US FTA negotiations — and chief of staff.

By the time he became secretary of state, Negroponte says, Baker was tough, determined and competitive “not only with foreign counterparts but also with colleagues on the home front.” He chose carefully which battles to fight and then focused every sinew to win. She approvingly quotes former Defense Secretary Bob Gates’s assessment of Baker as “a master craftsman of the persuasive and backroom arts at the peak of his powers.”

Baker needed all these talents. The results after four years were: pushing Saddam Hussein out of Kuwait, the launch of UN peace negotiations to help end civil wars in Central America, the reduction of the threat of nuclear war, the bringing together of the leaders of Israel and the Palestinian Territories to meet face to face; freedom for East European nations; and the unification of Germany, anchored within NATO.

Why did Baker succeed?

First, he had the full confidence of his president. As Negroponte observes: “He was so close to the president that each could finish the other’s sentence.” Bush conferred with him every day and Baker wrote a nightly report that was “honest, if not blunt”, in keeping the president informed. Importantly, Bush, National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft and Baker kept their differences among themselves, resolving distinct approaches to policy through internal debate and achieving consensus before communicating a final decision.

Second, as Negroponte observes, Baker was a master negotiator, a pragmatic realist who also believed in concepts such as liberty, freedom and democracy. He pursued the traditional US policy of working with allies and international institutions to reassure them of US steadfastness while at the same time creating a firm basis upon which to negotiate with Moscow on arms control and regional issues. Baker’s goal was to establish the United States as a leader of democratic ideals and influence, a purpose that Bush named a “New World Order.” “A world where the rule of law supplants the rule of the jungle,” Bush said in an address to a joint session of Congress on September 11, 1990. “A world in which nations recognize the shared responsibility for freedom and justice. A world where the strong respect the rights of the weak.”

Bush and Baker confirmed the priority of good bilateral relations by making their first foreign trip as president and secretary to Ottawa in February, 1989. They met with Prime Minister Brian Mulroney, who had just seen Gorbachev, and discussed the general secretary’s likelihood of success in carrying out his reforms. Mulroney also understood the importance of relationships and, if anything, the Canada-US entente grew even closer, and Canada achieved its long-sought Acid Rain Accord.

Third, originally dismissive of the bureaucracy, Baker came to rely on and trust his State Department. He removed Reagan’s political appointees and rotated-in foreign service officers, preferring men and women who would think creatively to face the challenges of 1989 and beyond. Baker’s deputy, Lawrence Eagleburger, was a career foreign service officer, who would succeed him as secretary for the last two months of the Bush administration.

James Baker worked hard. When one avenue closed off, he found another. He was not a strategic thinker like Henry Kissinger, but he was deliberative, possessing a fine grasp of complex facts and a better sense of politics than Kissinger. Baker’s years in government gave him experience in foreign affairs. Focused and disciplined, he had also developed a superb global network of presidents, prime ministers, foreign and treasury ministers. He had no compunction about calling in chits. In Negroponte’s assessment, Baker was a man of action who pursued the logic of his decisions with determination and persistence

James Baker did not succeed on all he put his hand to – the Middle East remained intransigent. He left Yugoslavia to the Europeans, who promised to fix things, but Yugoslavia imploded. Post-Tiananmen China did not break the long-term US economic interests with the Peoples Republic but critics argue that human rights were left behind.

But in the one big thing — sorting out the dissolution of the Soviet Union and avoiding loose nukes — he succeeded. For a generation, we slept more comfortably.

Baker fits into that cohort that Walt Isaacson and Evan Thomas described as the American “wise men”. They took on the burden of first designing and then sustaining our rules-based multilateral system based on liberal principles of democracy and open markets. For those of us born after the Second World War, the rules-based order has given humanity relative peace and security unknown to previous generations.

While now fraying, that system owes much to American leadership, statecraft and diplomacy. Freedom of navigation is guaranteed by the US Navy and collective security is guaranteed by alliances, notably NATO, for which Americans still shoulder most of the burden. The US taxpayer also pays a heftier share in supporting the multilateral institutions – the UN and its alphabet soup of agencies, the International Monetary Fund and World Bank, and the World Trade Organization.

Driven by duty, devotion and patriotism, Americans like Baker aimed to make the world a better place. Others, including Canadians, helped engineer this remarkable experiment in global order, but the Americans were the architects.

As Negroponte demonstrates, James Baker proved to be a “master negotiator” in ensuring it endured with the end of the Cold War. We can only hope for more like Baker as we enter into a new epoch that, for now, is both messy and mean.

Contributing Writer Colin Robertson, a former career diplomat, is a Fellow and Senior Adviser with the Canadian Global Affairs Institute in Ottawa.